School Resources

What Was the Stop the Seventy Tour?

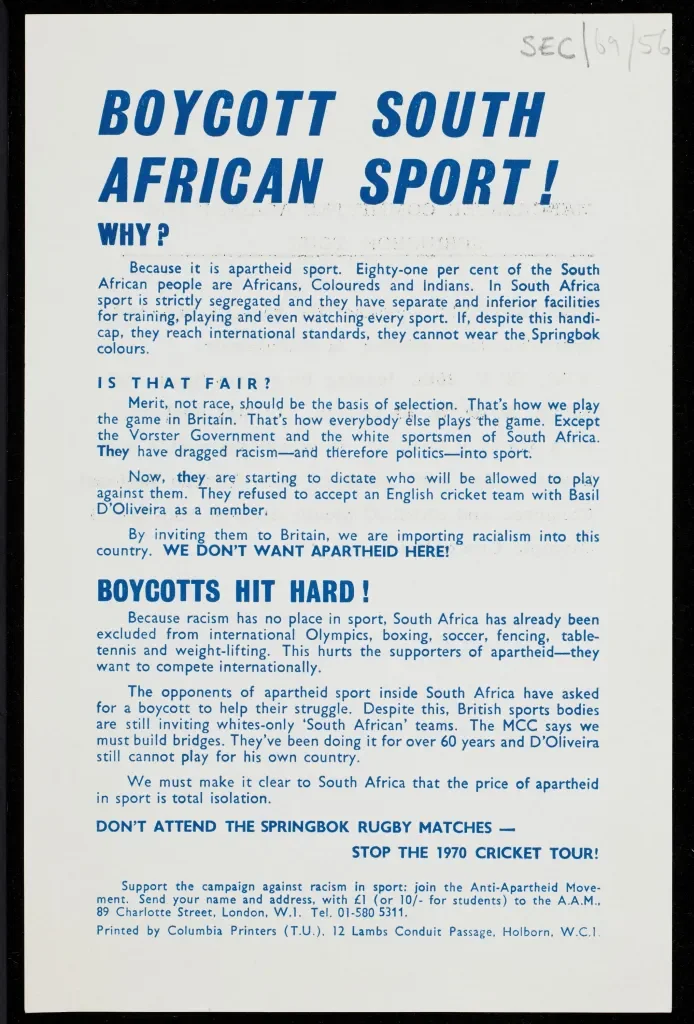

The Stop the Seventy Tour (STST) was a campaign led by the Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM) and activists like Peter Hain. Their goal: to disrupt every game of the Springbok rugby tour and pressure British authorities to cancel the planned South African cricket tour of 1970.

This was one of the largest direct action protest campaigns in British history.

Key Players in the Movement

Indian Workers’ Association (IWA): A powerful anti-racist group of South Asian workers based in the Midlands. Under Jagmohan Joshi, the IWA linked apartheid in South Africa with racism at home in Britain.

Pete Loewenstein, a student from Nottingham and originally from South Africa, helped organise protests including a power cut at a rugby match in Leicester. He shouted at players in Afrikaans and raised banners with his group.

Multiracial Coalitions: The protests involved Black, Asian, and white British activists—including trade unionists, students, and church leaders.

What Happened at the Matches?

Floodlights were cut at one match in Leicester.

Banners were unfurled inside stadiums calling the players “racists.”

Protesters were dragged out by police—some beaten out of view.

In Manchester, police used horses and removed ID badges to avoid accountability.

Why Did This Matter?

It broke the idea that sport and politics are separate.

Protesters argued that apartheid made sport political already.

It connected global injustice with local racism.

The IWA showed how discrimination in Britain and South Africa were part of the same system.

It led to real change.

South Africa’s cricket tour in 1970 was cancelled.

South Africa was expelled from the Olympics and major international sporting bodies.

Discussion Questions

Why do you think activists chose to protest rugby and cricket matches?

What role did organisations like the IWA play in connecting global and local struggles?

Why was this protest described as a “moral panic” in Britain?

What can this campaign teach us about the power of collective action?

Key Terms

Term Definition

Apartheid A system of racial segregation in South Africa from 1948 to the early 1990s

Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM) British-based group opposing apartheid and racism

Indian Workers’ Association (IWA) A Midlands-based anti-racist and pro-worker organisation of Indian migrants

Stop the Seventy Tour Campaign to stop South Africa’s 1969–70 sports tour in the UK

Moral Panic A widespread fear or reaction to a perceived threat to societal values

Activity

Design a Protest Poster:

Create a poster that could have been used in the 1969–70 campaign. Include:

A bold slogan (e.g. “No Normal Sport in an Abnormal Society”)

A visual message (flag, sport image, protest)

A short explanation of what your poster aims to communicate

When Rugby Was War: How Anti-Apartheid Protesters Fought South Africa’s Sporting Pride — and Won

In the winter of 1969, a rugby match in Leicester transformed into a lightning rod for a nation in flux. As South Africa’s all-white Springboks team took the field at Welford Road, a group of student protesters , including South African émigré and Nottingham University students Pete Loewenstein and Benny Bunsee, executed a bold act of sabotage: they cut power to the floodlights.

The disruption, brief but symbolic, was not just about a rugby match. It was part of a sweeping, coordinated campaign, the Stop the Seventy Tour, designed to isolate apartheid South Africa from the international sporting arena. What began as a protest by civil society elites evolved into a mass grassroots movement, uniting trade unionists, students, faith leaders, and immigrant communities under one banner: No Normal Sport in an Abnormal Society.

At the center of this mobilisation was the Indian Workers’ Association (IWA). Long a fixture in Britain’s anti-racist and anti-imperialist struggles, the IWA, led by fiery Birmingham-based organiser Jagmohan Joshi, saw the Springboks' tour not simply as a foreign affairs issue, but as an extension of the racism many South Asians and Afro-Caribbeans faced at home.

“You can’t cheer for apartheid on the pitch and pretend it’s not alive in the streets,” Joshi remarked at a rally in late 1969. The IWA mobilised workers across the Midlands to support the protests, forging alliances with student groups and radical clergy. For Joshi, the campaign against South African sport was inseparable from struggles against housing discrimination, police harassment, and the Powellism that gripped British political discourse.

A Nation on Edge

The 1969–70 protests marked a chaotic and violent high point in Britain’s anti-apartheid movement. Across 23 rugby matches in cities like London, Swansea, Manchester, and Leicester, activists staged sit-ins, pitch invasions, and clashes with police. Some were beaten, many were arrested. The protests were unprecedented in scale and coordination.

What unfolded was more than a sports boycott — it was what some historians now describe as a “moral panic.” In postcolonial Britain, fears over student radicalism, permissive youth culture, Black Commonwealth immigration, and the unraveling of empire converged into a reactionary backlash. Media outlets painted the demonstrators as enemies of order. The police and the state worked to criminalise and depoliticise the protests, often portraying them as threats to democracy itself.

But repression had a paradoxical effect: it galvanised. The campaign against the Springboks — and the subsequent cancellation of South Africa’s 1970 cricket tour — drew in a broad, multiracial coalition. It was the moment when anti-apartheid sentiment moved from elite diplomacy to mass, street-level action, animated by the lived experiences of racism in Britain.

Protest, Performance, and Power

In Leicester, Loewenstein and 20 others smuggled banners into the stadium and heckled the players in Afrikaans. “Go home, you racists,” he shouted before being removed by police. Later, in Manchester, he photographed officers who had deliberately removed their ID numbers — a stark sign of growing authoritarian tactics.

The campaign redefined the boundaries of political protest. Sit-ins at rugby stadiums became performative acts of resistance, blending civil disobedience with political theatre. Protesters challenged not just apartheid but the illusion that sport was separate from politics.

For Joshi and the IWA, the protests offered a powerful lens to frame anti-racism as both global and local. They demonstrated that opposition to apartheid was not just about South Africa — it was about who belonged in Britain, whose voices were heard, and whose lives mattered.

A Movement from Below

By 1990, South Africa had been expelled from nearly every major international sports body. But the seeds of that isolation were planted two decades earlier — in moments of resistance like those in Leicester and Manchester.

What made the Stop the Seventy Tour different was not only its tactics but its moral clarity. It showed that ordinary Britons — from African-Caribbean dockers in London to Indian textile workers in Birmingham — were willing to disrupt business as usual to fight injustice, wherever it lived.

And it proved that the playing field — once seen as apolitical — could be reclaimed as a site of profound political struggle, a place where the fight for justice played out not just in laws or courts, but under floodlights, in the cold, with banners raised.