Workshop Title: “Rocking the System: How Youth Fought Racism with Music and Leaflets”

Learning Objectives

By the end of the session, students will:

Understand the rise of anti-racist youth movements in the 1970s (SKAN, RAR, ANL)

Explore how music and grassroots campaigns influenced political and social change

Discuss the power of youth voices and draw links to modern activism (e.g. Black Lives Matter, climate justice)

Create their own anti-racism campaign materials

Duration: 60–90 minutes

Part 1: Setting the Scene (15 mins)

Starter Discussion (5 mins):

Ask: “What kinds of music or art do you think can inspire change?”

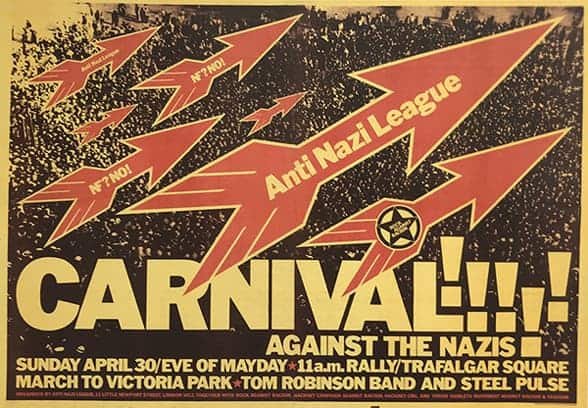

Show images of Rock Against Racism gigs, SKAN leaflets, and 1970s protests.

Mini History Presentation (10 mins):

Briefly explain:

The rise of the National Front in the 1970s

Eric Clapton’s speech and the formation of Rock Against Racism

SKAN (School Kids Against the Nazis) and how students joined the movement

Punk, reggae, and protest as tools for unity

Include primary sources:

Copy of a real SKAN leaflet

Quote from a former SKAN member: “We weren’t members. We just believed racism was wrong—and SKAN leaflets said it loud.”

Quote from Steel Pulse: “We had to fight to play music—and be safe doing it.”

Part 2: Activity Stations (30 mins)

Divide the class into 3 groups. Each group rotates through the following 10-minute stations:

Station 1: Protest Playlist

Listen to short clips of music from:

The Clash (“White Riot”)

Steel Pulse (“Ku Klux Klan”)

Tom Robinson Band (“Glad to Be Gay”)

Discuss: What messages do you hear? How does the music make you feel?

Station 2: Design a Leaflet

Show examples of SKAN leaflets.

Ask students to create their own anti-racism flyer using slogans, headlines, and simple artwork.

Prompts: “If you were resisting hate in your school, what would your leaflet say?”

Station 3: Debate Circle

Pose this statement: “Politics doesn’t belong in music.”

Let students debate for and against, using what they’ve learned.

Part 3: Reflection & Creative Output (15 mins)

Ask students to answer:

What surprised you most today?

What would you have done if you were in school in 1979?

Optional:

Write a short letter to a future student explaining why anti-racist activism still matters.

Share one thing you could do this week to promote inclusion.

Materials Needed

Speakers or audio device for music

Printed SKAN leaflets and posters

Art supplies for leaflet design (or digital tools)

Projector for images or video clips

Flipchart or whiteboard

Extension/Homework

Research a modern campaign that uses music or youth activism to fight injustice (e.g. Stormzy’s activism, Fridays for Future, etc.)

Create a “Zine” or digital poster to compare SKAN with a current youth-led movement

SKAN and the Sound of Youth: When Schoolkids Took On the Nazis

In 1978, a time when the far right National Front was gaining votes and visibility across Britain, something unexpected was circulating in school corridors: a leaflet bearing the words “School Kids Against the Nazis”, or SKAN. It was raw, direct, and subversive—a youth led publication that declared, simply but fiercely, that racism would not go unchallenged.

The leaflet, like many of Rock Against Racism and its sister group the Anti Nazi League bulletins, did not shy away from profanity. It used the F word, stirred controversy among some celebrities who had initially supported the Anti Nazi League (ANL), and became a small but resonant flashpoint in a larger struggle over identity, culture, and belonging. “The message on this one,” recalled one who received it, “was that if the NF ever got into power then a lot of our favourite pop stars would be deported for being black, Asian—or having one or both parents from outside the UK.”

Even for students who didn’t identify closely with any political group, SKAN’s leaflets mattered: their blunt tone, their uncanny ability to confront fear, and their placement in classrooms and playgrounds made them feel seen—and challenged. “If there was an organisational structure,” one former recipient later said, “I never knew it. I thought maybe it was tied to the Socialist Workers Party, but none of that seemed to matter. What mattered was the leaflets, and what they dared to say.”

Music, Mobilisation, and the Rise of Rock Against Racism

SKAN did not emerge in a vacuum. Since the formation of Rock Against Racism (RAR) in 1976, youth culture had become a battleground. RAR was born when Eric Clapton, performing in Birmingham, praised Enoch Powell — symbolising the mainstream tolerance of racist rhetoric. RAR sought to reclaim music as a space of resistance. By 1979, as the general election loomed and tensions with the National Front intensified, RAR’s Militant Entertainment Tourcrisscrossed Britain with a bumper crop of punk, reggae, and new wave bands speaking out against the rising tide of xenophobia.

In Birmingham, the RAR tour reinforced what groups like SKAN had already sensed: that culture—music, fanzines, leaflets—could politicize young people in ways that politics alone could not. The city’s diverse youth stood together, dancing, singing, protesting with badges, slogans, and banners. Bands such as Steel Pulse lent the tour an authentic, local resonance; their lyrics were grounded in the everyday experiences of Black Britons in Handsworth, Sparkbrook, and across the Midlands.

SKAN, ANL, and Grassroots Voices

SKAN was effectively the “naughty cousin” of the Anti Nazi League—a more anarchic, school based version. It pushed at boundaries, challenged comfort zones, and refused the idea that separation or silence could be a defense. SKAN’s messages travelled through students: leaflets passed in corridors, lunchtime debates, playground conversations. It gave voice to those who felt the National Front was not just a problem elsewhere, but something encroaching in their schoolyards, passing buses, and homes.

One former SKAN recipient remembers that while many celebrities publicly pulled back their support from ANL over SKAN’s raw language, the students didn’t care. One name that did cause a stir was Brian Clough, the outspoken football manager—the reverence many youth had for Clough meant his stance carried symbolic weight.

Legacies in Loud and Quiet Form

Though SKAN’s life was relatively brief—it faded from view around 1979—its impact endured. It exemplified how young people could take culture, fear, and outrage, and turn them into something collective. It fused with RAR, with ANL, with Kids Against Racism and Gays Against Racism. It shaped an era in which pop charts, punk gigs, reggae rhythms, leaflets, and classmate chatter all became vectors of resistance.

SKAN reminds us that anti racism in Britain was not only led by union halls, churches, or political parties—but by schoolkids armed with leaflets, fierce sincerity, and the conviction that injustice said too much to remain silent.