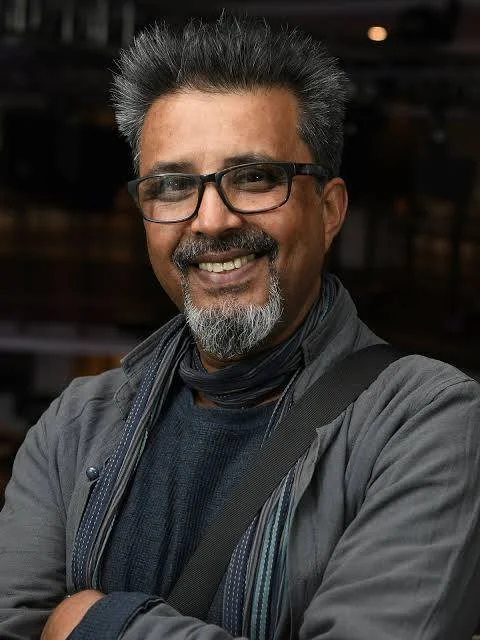

Muktar Darr

Q1. Could you outline your early influences and how they shaped your political and cultural trajectory?

I was born in Pakistan and grew up in Birmingham from the 1960s onwards. My father was a trade unionist in the foundries, and I came of age amidst racism, police harassment, and National Front activity. At school, I experienced racist bullying daily; outside, we were constantly aware of “Paki-bashing.” Those formative years instilled a strong sense of injustice and the need to resist. By the 1970s, I was active in school strikes, youth groups, and anti-racist mobilisations, drawing inspiration from Black Power, Malcolm X, and the struggles of African American communities, as well as the anti-colonial currents running through Britain’s South Asian diaspora.

Q2. How did your political activism begin to take form in the Midlands context?

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Birmingham and the Midlands were flashpoints of anti-racist struggle. I was involved in campaigning against police stop-and-search (the “Sus” laws), in Asian Youth Movements, and in cultural initiatives that sought to empower local communities. We understood racism as structural—embedded in housing, employment, and education—not just interpersonal prejudice. The uprisings of 1981 across Brixton, Handsworth, Toxteth and elsewhere reinforced that our struggles were part of a wider national movement.

Q3. What role did the Asian Youth Movements (AYMs) play in shaping your activism?

The AYMs were crucial. They emerged across northern and midland cities—Bradford, Sheffield, Birmingham, Nottingham—articulating a politics of self-defence, dignity, and anti-racism. We consciously used the label “Black” politically, as solidarity across Asian, African, and Caribbean communities. Our motto was often “Self-defence is no offence.” AYMs challenged police harassment, deportations, and the rise of the far right, but also engaged in cultural work—posters, newsletters, murals—that celebrated our histories. These movements gave me grounding in both direct action and the importance of cultural expression as a political tool.

Q4. Can you describe your involvement in the arts and how it intersected with activism?

In the mid-1980s, I began working at the Birmingham Arts Lab and later the Midland Arts Centre. I curated exhibitions and film programmes highlighting African, Asian, and Caribbean artists. My approach was to use culture as a form of resistance—creating spaces where our stories could be told and challenging the marginalisation of Black and Asian artists in mainstream institutions. I worked with collectives like the Black Audio Film Collective, Sankofa, and with poets and visual artists whose work interrogated race, memory, and belonging. Art was never separate from activism—it was a vehicle to engage communities, document our histories, and assert alternative narratives.

Q5. You’ve been linked to significant exhibitions. Could you speak about their political dimensions?

One important project was programming Handsworth Songs by the Black Audio Film Collective in Birmingham after the 1985 uprisings. It created intense debate—many felt it spoke directly to the lived experiences of police violence and racism. Another was curating exhibitions with South Asian and African Caribbean artists that tackled themes of displacement, memory, and cultural survival. These were never neutral displays: they were interventions into ongoing debates about race, identity, and belonging in Britain. At MAC and the Arts Lab, we often faced hostility from management or funders who felt this work was “too political.” But for us, art had to speak to the realities of our communities.

Q6. How did anti-racist cultural activism connect to broader political struggles of the time?

The 1980s were marked by Thatcherism, deindustrialisation, and a hardening of racist state policies—immigration controls, the 1981 British Nationality Act, police militarisation. Cultural activism was a way of contesting these. We linked exhibitions to campaigns, for example against deportations or racist policing. Cultural events became organising spaces: screenings, poetry nights, art shows would double as political forums. This was also the era of the miners’ strike (1984–85), which connected us to working-class struggles across racial lines. There was genuine solidarity between striking miners and Asian youth activists, particularly in the Midlands and Yorkshire.

Q7. Could you elaborate on the international dimensions of your work?

Our politics were always internationalist. We saw ourselves in solidarity with liberation struggles in South Africa, Palestine, and across the Global South. Many of us were involved in anti-apartheid campaigns; I helped organise boycotts and cultural events amplifying South African artists. We were equally attentive to South Asian politics—the Emergency in India, the Bangladesh war, and repression in Pakistan. Culturally, this meant we drew inspiration from reggae, dub poetry, and South Asian musical traditions, mixing them in our cultural events. Diasporic art was understood as part of a global struggle against racism and imperialism.

Q8. What challenges did you face in bringing anti-racist cultural work into mainstream arts institutions?

Institutional racism was pervasive. Galleries and theatres often treated Black and Asian art as marginal, or “community outreach,” never as central to British culture. We fought constantly for funding, space, and recognition. Exhibitions were sometimes censored or toned down; management resisted explicitly political framing. At the same time, within our communities, there was scepticism about art—seen as elitist or detached. The challenge was to make art relevant: holding events in accessible spaces, linking shows to lived struggles, involving young people.

Q9. Could you talk about the importance of archives and memory in your work?

Archiving has been central. Too often, our struggles and cultural productions were undocumented or erased. I kept posters, leaflets, catalogues, and recordings, knowing how fragile this history was. Later, I worked with community archives to preserve Asian Youth Movement materials, photographs of protests, and records of exhibitions. Memory is political: if we don’t document, our histories will be written out. For me, archiving is part of activism—it ensures future generations know these struggles existed, that we resisted.

Q10. What were the key lessons from the 1980s for today’s activists and artists?

First, solidarity matters. The political Black framework enabled unity across communities, which was crucial in fighting state racism and fascism. Second, culture is not decorative—it’s a weapon. Art, music, film, and writing shaped consciousness and built collective identity. Third, independence is vital. While we sought funding, we also relied on self-organisation—DIY publications, voluntary labour, shared resources. Finally, the lesson is that struggle is long-term. The racism we faced in the 1980s—police violence, state repression, far-right threats—echoes in today’s Windrush scandal, Prevent, and rising authoritarianism. The need for art and activism to intertwine is as urgent as ever.

Q11. How do you see your legacy and ongoing commitments?

I see my role as part of a collective, not an individual legacy. The work of the Asian Youth Movements, Black cultural collectives, and community campaigns shaped a generation. My commitment remains to making these histories visible—through exhibitions, writing, archiving—so younger activists can draw strength. I also mentor emerging artists and curators of colour, sharing experiences of navigating institutions, sustaining integrity, and grounding art in communities. The struggle continues, but it is heartening to see younger generations picking up the mantle, connecting racial justice with climate justice, migrant rights, and decolonial movements.