Avtar Jouhl

Interviewer: Can you start by telling me where you were born and a bit about your family?

Avtar Singh Jouhl:

I was born in 1937, in a village called Jandiala, in Punjab, in India. My father was Lakha Singh Johal and my mother was Banti Kaur. They were both farmers. Subsistence farmers. Neither of them could read or write. There were five of us children—four sons and one daughter—and I was the only one who went to school. The only one who received formal education.

Interviewer: What was it like growing up there?

Jouhl: It was a political time. We were living under late colonial rule, and repression was normal. You were aware of it even as a child. One of the things that stayed with me was that one of my cousins was imprisoned for five years during the 1940s because of political activism. That had a big impact on me. You understood very early that politics was serious. It wasn’t theoretical.

At school, at Khalsa High School, I was already organising. I opposed the introduction of school fees, because I didn’t think education should depend on money. And I challenged child labour. It was accepted as normal, but I didn’t accept it.

Interviewer: When did your political involvement become more formal?

Jouhl: In 1953 I went to Lyallpur Khalsa College in Jalandhar. That’s when I became active in the Student Federation of India. I was also undergoing political training, with the intention of joining the Communist Party of India. In 1955 I was arrested briefly because of my political activities.

That same year my father died. I was sixteen. Later that year I married my wife, Manjit Kaur. Because of my political work, and the risks to my family, I later changed the spelling of my surname. It was about protection.

Interviewer: What brought you to Britain?

Jouhl: I came to Britain in 1958. Originally, I planned to study at the London School of Economics. That was my intention. But when I arrived, I saw something very different. I witnessed the race riots in Nottingham and Notting Hill in 1958. That made things very clear.

I visited my brother in Smethwick, and I took a job as a moulder’s mate at Shotton Brothers foundry. I was working alongside other Asian and Black workers. The conditions were terrible. There was racism everywhere—at work, in housing, in everyday life. So I decided not to go to university. I stayed in the Midlands instead, because I felt the work needed to be done there. My wife joined me in Britain in 1960.

Interviewer: How did you become involved in organised politics here?

Jouhl: I joined the Communist Party of Great Britain soon after arriving. I was encouraged by Jagmothan Joshi and Maurice Ludmer. Through Joshi, I became involved in the Indian Workers Association—the IWA. At that time it was the largest organisation representing Indian workers in Britain. Tens of thousands of members.

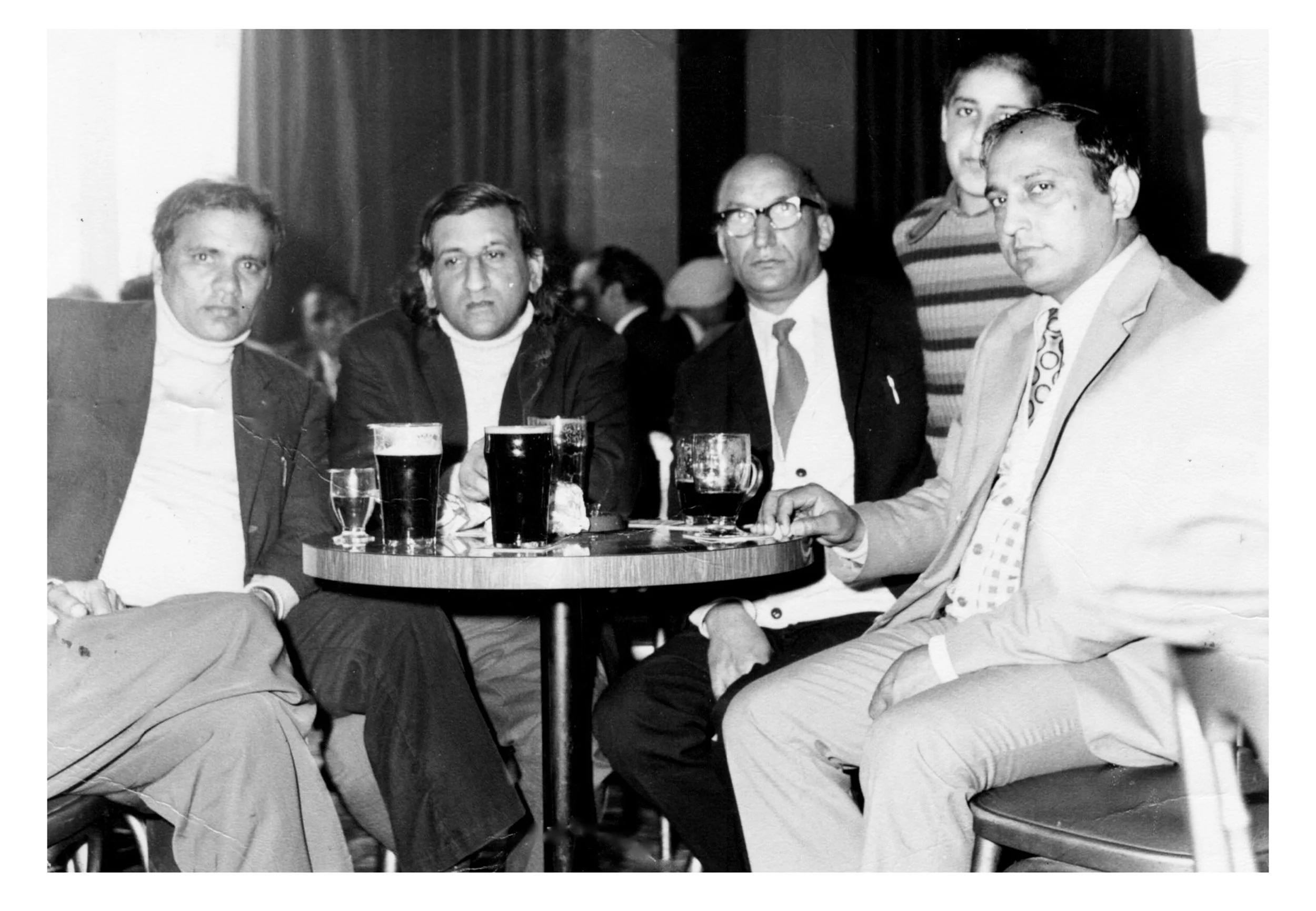

I became general secretary of the IWA from 1961 to 1964. Then I was national organiser from 1964 until 1979. And then I became general secretary again from 1979 until 2015. Alongside Joshi, Ludmer, Shirley Fossick—who later became Shirley Joshi—and Manu Manchanda, we formed a core group. We were involved in anti-racist and anti-imperialist struggles, especially in the 1960s.

Our work was internationalist. We had connections with people across Europe, Africa, the Caribbean, and the United States. That included Martin Luther King, Claudia Jones, Paul Robeson, Stokely Carmichael, and Malcolm X.

Interviewer: Can you talk about Smethwick in the 1960s?

Jouhl: The 1964 general election in Smethwick was extremely racist. One of the most openly racist campaigns in British history. The Conservative candidate, Peter Griffiths, endorsed racist slogans that were being circulated by people like Colin Jordan. After the election, things got worse. There were reports of burning crosses. There was even a Ku Klux Klan presence locally.

As the IWA, we had to respond. One of the most important things we did was to invite Malcolm X to Smethwick. That was deliberate. We wanted to connect the local struggle to a global struggle. I walked with Malcolm X down Marshall Street. There’s a blue plaque there now, but at the time it was dangerous. It was necessary.

Interviewer: What was workplace organising like during that period?

Jouhl: Workplaces were segregated. Very openly. There were ‘white only’ toilets. One of the things I did was to encourage workers to use those facilities anyway, to force desegregation.

At the Midland Motor Cylinder Company, at the Birmid works, I challenged trade union rules that said shop stewards had to have a ‘sufficient command of English’. That rule was racist. It was designed to exclude Asian workers from leadership. These were difficult struggles.

Later, at Dartmouth Auto Castings, during the 1970s and 1980s, I made sure the IWA remained central to anti-racist organising in the Midlands.

Interviewer: How did your role change later on?

Jouhl: After more than thirty years working in foundries, I retired and moved to Solihull. In the mid-1990s I became a lecturer at the Birmingham Trade Union Studies Centre. Later I taught trade union rights at South Birmingham College. Teaching was another form of organising.

Things did change over time. In the early 1960s, Black workers were often ignored by trade unions. By the 1990s, we were supporting Black leadership. I supported the election of Bill Morris as general secretary of the Transport and General Workers’ Union. Through the IWA, we also supported Asian women’s activism, including during the Imperial Typewriters and Grunwick disputes, and mobilised women against the Immigration Act of 1981.

Interviewer: What do you feel most proud of?

Jouhl: During the Thatcher years, when deindustrialisation was destroying communities, we helped set up the Shaheed Udham Singh Welfare Centre on Soho Road in Birmingham. It opened in 1978. It’s still operating today.

During the miners’ strike in 1984–85, I helped organise solidarity. We arranged transport for hundreds of IWA members to go to mining communities across the country.

In later years, I became very concerned with preserving history. I donated my papers to the Wolfson Centre at Birmingham Library. I worked with writers like Kit de Waal, and with Banner Theatre. These histories need to be remembered.