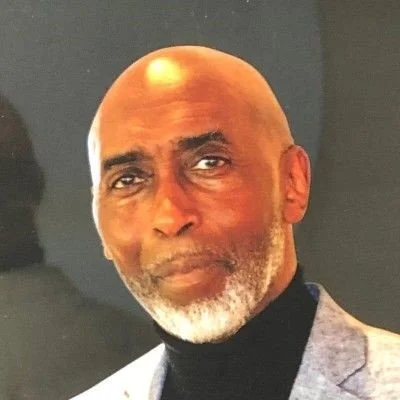

Paul Pryce

I first came into contact with the African Caribbean Cultural Foundation through education rather than art. At the time, ACFF was running African Studies courses, and that was my entry point. What attracted me was that it was African-centred. It wasn’t trying to squeeze African history into a European framework; it was starting from Africa itself, from African civilisations, African philosophy, African knowledge systems.

That was important, because at school and university those things just weren’t there. What we were being taught was partial, and often distorted. ACFF filled that gap. It was about supplementing what wasn’t provided in mainstream education, but also challenging the idea that this knowledge was somehow secondary or optional.

The teaching methods were very different from what I’d experienced elsewhere. It wasn’t hierarchical in the same way. People brought their own knowledge, their own experiences, and those were treated as valid. There was a strong sense that education was political — not party political, but about consciousness, self-definition, and understanding your position in the world.

We weren’t just learning dates or events; we were learning how colonialism worked, how knowledge had been shaped, and how that affected Black people in Britain. That was empowering. It gave people language and frameworks to understand their own lives.

ACFF wasn’t only about adults. One of its most important roles was in supplementary education for children. Saturday schools were central. They provided African and Caribbean history, language, culture — things children weren’t getting in mainstream schools.

This wasn’t just about pride, although that mattered. It was about confidence and critical thinking. Children could see themselves reflected positively in what they were learning. Parents understood that this kind of education was necessary because the school system wasn’t neutral — it carried its own biases and omissions.

Although education was the main focus, cultural activity was always part of ACFF. There were exhibitions, performances, talks, and events marking Black History Month long before it became mainstream or institutionalised.

But culture was never separate from education. Art wasn’t treated as decoration or entertainment; it was part of the learning process. Artists, writers, and musicians contributed to political education. You’d come to an exhibition and leave having learned something — about history, struggle, or contemporary issues.

Over time, tensions emerged around governance and leadership. There were different views about the direction ACFF should take, especially as funding became more prominent. Once money enters the picture, expectations change — from funders, from local authorities, from cultural bodies.

There was pressure to professionalise, to become more like a conventional arts organisation. Some people welcomed that; others were concerned it would dilute the original mission. There were debates about who should lead, who represented the community, and how accountable leadership was.

The transition from ACFF to what became the New Art Exchange was significant. The New Art Exchange is a very different kind of institution — purpose-built, architecturally striking, and positioned within the mainstream cultural sector.

There were gains, of course: visibility, resources, a platform. But there were also losses. Something about the grassroots, educational focus of ACFF didn’t fully carry over. The emphasis shifted more towards exhibitions and programmed culture rather than sustained community education.

I think it’s important to recognise that these institutions didn’t come out of nowhere. New Art Exchange sits on foundations laid by organisations like ACFF, even if that history isn’t always visible.

Looking back, ACFF played a crucial role in shaping people’s lives. Many who went through its courses or schools went on to become teachers, artists, youth workers, and community organisers. Its impact can’t be measured only in exhibitions or events; it’s visible in people.

What ACFF showed was that Black communities didn’t just need representation — they needed control over knowledge production. That’s a lesson that still matters today.

Education was always at the heart of it for me. Culture mattered, but culture without consciousness doesn’t take you very far. ACFF understood that. It treated learning as a collective process and saw cultural work as inseparable from political understanding.

That’s something I think we’ve lost sight of in some contemporary cultural spaces.